Learning Rate Schedulers

Different learning rate schedulers and their implementation in python

Introduction

Many students and practitioners primarily focus on optimization algorithms for how to update the weight vectors rather than on the rate at which they are being updated. Nonetheless, adjusting the learning rate is often just as important as the actual algorithm. Learning rate ($\eta$) (LR) as a global hyperparameter determines the size of the steps which a GD optimizer takes along the direction of the slope of the surface derived from the loss function downhill until reaching a (local) minimum (valley).

Choosing a proper LR can be difficult. A too small LR may lead to slow convergence, while a too large learning rate can deter convergence and cause the loss function to fluctuate and get stuck in a local minimum or even to diverge. Due to the difficulty of determining a good LR policy, the constant LR is a baseline default LR policy for training DNNs in several deep learning frameworks (e.g., TensorFlow, PyTorch). Empirical approaches are then used manually in practice to find good LR values through trials and errors. Moreover, due to the lack of relevant systematic studies and analyses, the large search space for LR parameters often results in huge costs for this hand-tuning process, impairing the efficiency and performance of DNN training.

But what if we wanted a learning rate that was a bit more dynamic than a fixed floating point number?

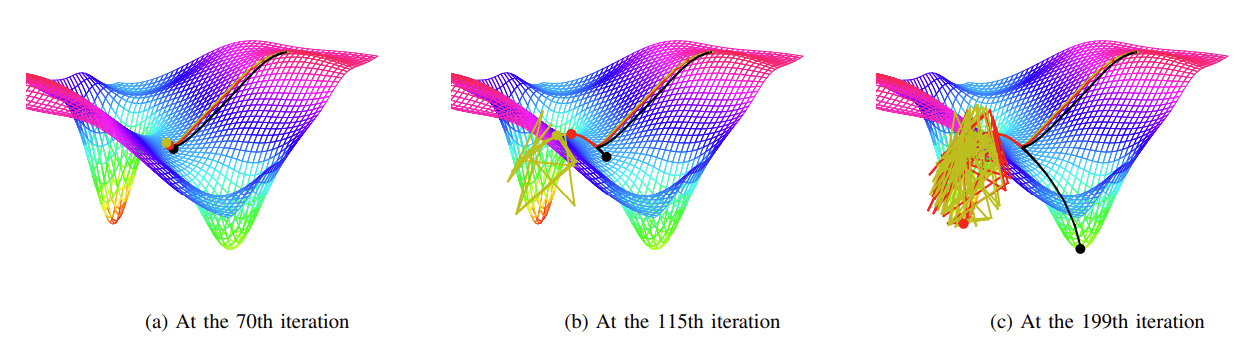

Numerous efforts have been engaged to enhance the constant LR by incorporating a multistep dynamic learning rate schedule, which attempts to adjust the learning rate during different stages of DNN training by using a certain type of annealing techniques.1 This is especially challenging, given that good LR schedules need to adapt to the characteristics of different datasets and/or different neural network models. Further, as seen below different LR policies will result in different optimization paths, since even though initially different LR functions product similar results, as the number of iterations increases the accumulated impact of the LR updates could also lead to sub-optimal results.2 It might be that high LRs introduce high “kinetic energy” into the optimization and thus model parameters are bouncing around chaotically.

In this post, we will review some learning rate functions and their associated LR policies by examining their range parameters, step parameters, and value update parameters. We will divide the LR schedulers into 3 categories: fixed, decaying, and cyclic.

Fixed Schedulers

The simplest LR scheduler is time-based. For example, step decay is scheduler that adjusts the learning rate after a fixed number of steps, reducing the learning rate by a specified factor. This is useful for situations where the learning rate needs to decrease over time to allow the model to converge.

The mathematical form of time-based decay is as follows:

Where $lr$, $k$ are hyperparameters and $t$ is the iteration number. In the Keras source code, the SGD optimizer takes a decay and lr arguments to update the LR by a decreasing factor each epoch3:

lr *= (1. / (1. + self.decay * self.iterations))

Here is an implementation of a similar fixed schedule called step decay, with the following mathematical formulation:

class StepLR:

def __init__(self, optimizer, step_size, gamma):

self.optimizer = optimizer

self.step_size = step_size

self.gamma = gamma

self.last_step = 0

def step(self, current_step):

if current_step - self.last_step >= self.step_size:

for param_group in self.optimizer.param_groups:

param_group['lr'] *= self.gamma

self.last_step = current_step

optimizer = # SGD, Adam, etc.

scheduler = StepLR(optimizer, step_size=30, gamma=0.1)

for epoch in range(num_epoch):

# train...

scheduler.step(epoch)

Decaying Schedules

One of the most widely used decaying schedulers is exponential decay: This scheduler adjusts the learning rate by a specified factor after each iteration. The learning rate decreases exponentially over time, which is useful for models that require a gradually decreasing learning rate. A use-case of this would be a larger learning rate to explore the loss surface and find one or more minima, where a slowing LR would help the loss function settle into the minimum rather than oscillating. It can be calculated as follows:

Where $lr$, $k$, are hyperparameters and $t$ is again the iteration number.

In the code below, in each epoch the step method updates the learning rate of the optimizer by

multiplying it with the decay rate raised to the power of the epoch number.

import math

class ExponentialLR:

def __init__(self, optimizer, gamma, last_epoch=-1):

self.optimizer = optimizer

self.gamma = gamma

self.last_epoch = last_epoch

def step(self, epoch):

self.last_epoch = epoch

for param_group in self.optimizer.param_groups:

param_group['lr'] *= param_group['lr'] * self.gamma ** (epoch + 1)

optimizer = # SGD, Adam, etc.

scheduler = ExponentialLR(optimizer, gamma=0.95)

for epoch in range(num_epoch):

# train...

scheduler.step(epoch)

Cyclic Schedules

Cyclic schedules set the LR of each parameter group according to cyclical learning rate policy where the policy cycles the LR between two boundaries with a constant frequency, as detailed in the paper by Leslie Smith.4

A classic example of such a scheduler is Cosine Annealing. This scheduler adjusts the learning rate according to a cosine annealing schedule, which starts high and decreases over time to zero. This is useful for models that require a gradually decreasing learning rate but with a more gradual decline in the latter stages of training.

import math

class CosineAnnealingLR:

def __init__(self, optimizer, T_max, eta_min=0):

"""

T_max:: the maximum number of steps over which the learning rate will decrease from

its initial value to eta_min

eta_min:: the minimum value of the learning rate

LR equation: eta_min + (1 - eta_min) * (1 + cos(pi * current_step / T_max)) / 2

"""

self.optimizer = optimizer

self.T_max = T_max

self.eta_min = eta_min

self.current_step = 0

def step(self):

self.current_step += 1

lr = self.eta_min + (1 - self.eta_min) * (1 + math.cos(math.pi *

self.current_step / self.T_max)) / 2

for param_group in self.optimizer.param_groups:

param_group['lr'] = lr

optimizer = # SGD, Adam, etc.

scheduler = CosineAnnealingLR(optimizer, T_max=100, eta_min=0.00001)

for epoch in range(num_epoch):

# train...

scheduler.step(epoch)

-

For example see Akhilesh Gotmare, Nitish Shirish Keskar, Caiming Xiong, & Richard Socher (2018). A Closer Look at Deep Learning Heuristics: Learning rate restarts, Warmup and Distillation_. CoRR, abs/1810.13243. ↩

-

Wu Y, Liu L, Bae J, et al (2019). Demystifying Learning Rate Policies for High Accuracy Training of Deep Neural Networks. https://arxiv.org/pdf/1908.06477.pdf ↩

-

https://github.com/keras-team/keras/blob/master/keras/optimizers/sgd.py ↩

-

Leslie N. Smith (2015). No More Pesky Learning Rate Guessing Games_. CoRR, abs/1506.01186. ↩