Probabilistic Generative Models- Variational Autoencoders (VAEs)

Understanding one of the most effective and useful process for generative modeling.

- Background

- The Main Idea of Variational Inference

- The Deep Learning Connection

- Towards (Deep) Generative Modeling

- Deep Variational Inference: VAEs

- VAE Evaluation

- Other Useful References

Background

In Bayesian models, the latent variables help govern the distribution of the data, where our ultimate goal is to is to approximate a conditional density of latent variables given observed variables.1 A Bayesian model draws the latent variables from a prior density $p(z)$ and then relates them to the observations through likelihood $p(x|z)$. Inference in Bayesian modeling amounts to conditioning on data and computing the posterior $p(z|x)$. In complex Bayesian models, this computation often requires approximate inference.2 For decades, the dominant paradigm for approximate inference was Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC). However, as data sets have become more complex and larger, we need an approximate conditional faster than a simple MCMC algorithm can produce. In these settings, variational inference provides a good alternative approach to approximate Bayesian inference.

[!note] MCMC and variational inference are different approaches to solving the same problem. MCMC algorithms sample a Markov chain; variational algorithms solve an optimization problem. MCMC algorithms approximate the posterior with samples from the chain; variational algorithms approximate the posterior with the result of the optimization.

Variational inference is suited to large data sets and scenarios where we want to quickly explore many models; MCMC is suited to smaller data sets and scenarios where we happily pay a heavier computational cost for more precise samples.

The Main Idea of Variational Inference

Rather than use sampling, the main idea behind Variational Bayesian (VB) inference is to use optimization.

VB methods allow us to re-write statistical inference problems (i.e. infer the value of a random variable given the value of another random variable) as optimization problems (i.e. find the parameter values that minimize some objective function).

First, we posit a family of approximate densities $\vartheta$, which is a set of densities over the latent variables. Then we try to find a member of that family that minimizes the Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence to the exact posterior,

| Finally, we approximate the posterior with the optimized member of the family $q^*(\cdot )$. One of the key ideas is to choose $\vartheta$ that is flexible enough to capture a density close to $p(z | x)$ but simply enough for efficient optimization. |

The Deep Learning Connection

An Autoencoder is a neural network designed to learn an identity function in an unsupervised way to reconstruct the original input while compressing the data in the process so as to discover a more efficient and compressed representation.

It consists of two networks:

- Encoder network: It translates the original high-dimension input into the latent low-dimensional code. The input size is larger than the output size.

- Decoder network: The decoder network recovers the data from the code, likely with larger and larger output layers.

The encoder network essentially accomplishes the dimensionality reduction. In addition, the autoencoder is explicitly optimized for the data reconstruction from the code. A good intermediate representation not only can capture latent variables, but also benefits a full decompression process.

The drawback with autoencoders is that their latent space may not have a well-defined structure or exhibit smooth transitions between classes that exist within the data. What if we wanted a smoother latent space that allowed for meaningful interpolation even between latent points?

Towards (Deep) Generative Modeling

Generative Modeling involves creating models of distributions over data points in some potentially high dimensional space. The job of the generative model is to capture dependencies between data points; the more complicated the dependencies, the more difficult the model is to train. Ultimately, we are aiming to maximize the probability of each point X in the training set under the entire generative process according to:

where $z$ is a vector of latent variables in a high dimensional space $Z$ that we can sample over according to a PDF. Then we have a family of deterministic functions $f(z;\theta)$ parameterized by $\theta$ where we want to optimize $\theta$ such that we can sample $z$ from $P(z)$ with a high probability that $f(z:\theta)$ will be like the X’s in our dataset. So before we can say that our model is representative of the dependencies in our data and thus representative of our dataset, we need to make sure that for ever point X there is a set of latent variables that causes the model to generate something very similar to X.

| It is important to note that in the above equation $f(z;\theta)$ is represented by a distribution $P(X | z;\theta)$ which enabled use to use the law of probability and the maximum likelihood framework to optimize our models through gradient descent. This would not be possible if we used $X = f(z;\theta)$ since it is deterministic and thus not differentiable. |

Deep Variational Inference: VAEs

VAEs take an unusual approach to dealing with this problem: they assume that there is no simple interpretation of the dimensions of $z$, and instead assert that samples of $z$ can be drawn from a simple distribution, i.e., N (0, I), where I is the identity matrix. With powerful function approximators like neural networks, we can simply learn a function which maps our independent, normally-distributed z values to whatever latent variables might be needed for the model, and then map those latent variables to X. All that remains is then to maximize $P(X)$ where $P(z) = N(z|0, I)$, using gradients.

Instead of mapping the input into a fixed vector, we want to map it into a distribution.

| In practice, for most $z$, $P(X | z)$ will be nearly zero and thus contribute nothing to our estimate of $P(X)$. It is also a large and expensive undertaking to search the entire space of possible $z$’s. So the key idea with VAEs is to attempt to sample values of $z$ that are likely to have produced X, and compute $P(X)$ just from those. This means we need a new function $Q(z | X)$ which can take a value of X and give us a distribution over $z$ values that are likely to produce X. The hope is that the space of $z$ values that are likely under $Q$ will be much smaller than the space of all $z$’s that are likely under the prior $P(z)$. |

![Source: [^3]](/My-DS-Blog/images/vae_dist.png)

So in our VAE setting, we have:

-

$p_\theta(x z)$ defines the generative model, playing the role of the decoder in a traditional autoencoder architecture -

$q_\phi(z x)$ is the probabilistic encoder, playing the role of encoder in a traditional autoencoder architecture.

The connection to deep learning, and why a VAE is an autoencoder, is that we use neural networks as our function approximators for $q$

| Our goal should be to make the estimated posterior $q_\phi(z | x)$ as similar to the real one $p_\theta(x | z)$ as possible (noted by the dashed blue line in the figure above). |

VAE Evaluation

Loss Function Derivation

So how do we do approximate inference of the latent variable $z$? We want to maximize the log-likelihood of generating real data ($log p_\theta(x)$) while minimizing the difference between the real and estimated posterior distributions. We can use Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence to quantify the distance between these two distributions. But more on that in a second.

So exact inference is not possible, and to see this we may use Bayes’ theorem to find an expression for the posterior:

The marginal term, or our denominator:

is intractable. So how do we get our posterior?

| Instead, we define an approximation $q_{\theta}(z | x)$ to the intractable posterior. To ensure that $p_{\theta}(z | x)$ is similar to $q_{\phi}(z | x)$, we could minimize the KL divergence between the two discrete distributions as an optimization problem: |

Or in the continuous case (and simplified notation):

| To see how we can start to minimize the KL divergence $\text{D}{\text{KL}}(q\phi(z | x) | p_\theta(z | x))$, we will reformulate eq. 4 above: |

So looking at eq. 5e we can see that the KL divergence depends on the intractable marginal likelihood $p_\theta(x)$ (note that we can drop the expectation for the second term since $q$ is not present). There’s no way we can minimize the above equation if we can’t write down $p_\theta(x)$ in closed form. However, we can get around this: we’ll minimize the KL divergence, but not directly. Instead, we try to find a quantity which we can maximize, and show that in turn this minimizes the KL divergence. The trick is not obvious, but is simply done by finding a lower bound on the log marginal likelihood.

Given that the second term in eq. 5e is fixed (the evidence term) as it does not depend on our surrogate $q$, we will derive a lower bound on the first term as a way of minimizing KL divergence

ELBO

In Variational Bayesian methods, this loss function is known as the variational lower bound, or evidence lower bound. The “lower bound” part in the name comes from the fact that KL divergence is always non-negative.

Recall the first term in eq. 5e, simply by rearraigning terms we get:

So adding eq. 6 back in to our KL divergence as $L(q)=L(\theta, \phi; x)$, we get we get:

Since KL divergence is a distance metric, we know that it must be greater than or equal to zero. Thus the evidence must be larger than $L$, hence the evidence-based lower bound. Finally, we can write the expression:

Which if true means that we have found the true posterior!

Maximizing the ELBO (to the point where eq. 8 holds) is equivalent to minimizing the KL divergence. That is the essence of variational inference.

ELBO (closed form)

Since the KL divergence is the negative of the ELBO up to an additive constant (with respect to q), minimizing the KL divergence is equivalent to maximizing the ELBO. Now we will seek to write the ELBO in closed-form, after which we will be able to implement the variational autoencoder.

Thus for a single data point $x^i$ the ELBO can be represented as:

The second term is the expected L2 reconstruction error under the encoder model. The firm term is thought of as a regularization term.

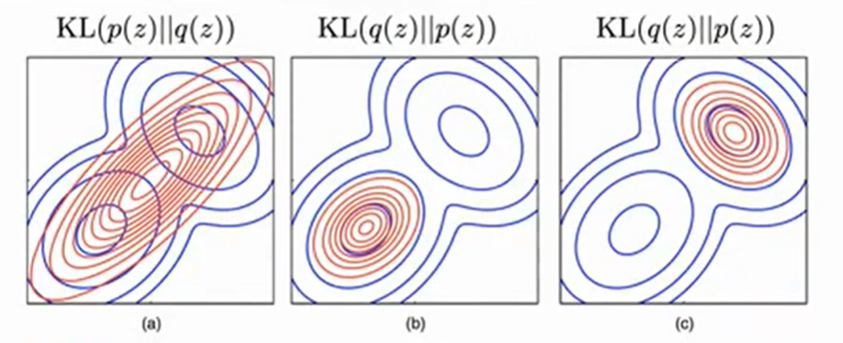

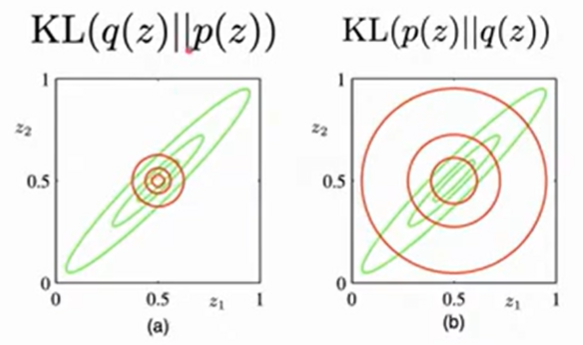

A Quick Detour- KL and Reverse KL

Hopefully you know that KL divergence is not symmetric: $KL(q(z)||p(z)) \neq KL(p(z)||q(z))$. Thus there is the forward KL $KL(q(z)||p(z))$ and the reverse KL $KL(p(z)||q(z))$ (forward and reverse are arbitrary here).

| *So why are we choosing $KL(q(z) | p(z))?$* The key is to understand the difference in behavior between the two different directions of the KL divergence. |

There are two main differences:

-

Mode seeking vs mode covering

-

Zero avoiding vs zero forcing

| Given that we are dealing with variational inference, and we are exploring a family of distributions $q$, we want to keep our search space as small as possible to maximize computational efficiency. Thus we choose $KL(q(z) | p(z))$ that has zero avoiding behavior- it does not place significant probability mass in regions of variable space that have very low probability, as seen above in Bishop’s Figure 10.2. |

| Similarly, we want to avoid mode-seeking behavior, like (a) in Bishop’s 10.3 above, since the center of that distribution falls between the two modes, thus assigning high probability to a region with low density (this means it is a bad representation of $p(z)$ ). This is significant since n practical applications, the true posterior distribution will often be multimodal, with most of the posterior mass concentrated in some number of relatively small regions of parameter space. These multiple modes may arise through non-identifiability in the latent space or through complex nonlinear dependence on the parameters. $KL(q(z) | p(z))$ tends to find one of these modes, while if we were to minimize the reverse instead, the resulting approximations would average across all of the modes and, in the context of the mixture model, would lead to poor predictive distributions (because the average of two good parameter values is typically itself not a good parameter value).3 |

Optimizing Our Loss Function

Why backpropogation does not work with our loss’s current form

Just as a refresher, let us recall that to minimize a function say $\mathbb{E}_{p(z)}[f(z)]$ we take the derivative, or in other words the expectation of the integral of the function. This works if our parameters are know. But say we had an equation like this with unknown parameters for $p$:

Minimizing this above function results in

So we have the gradient of two functions so using basic calculus we get:

The second term is not a problem since we can calculate the expectation of p with respect to the unknown parameters via sampling. What we can’t do is calculate the derivative with respect to unknown parameters like in the first term. In other words, we cannot swap the gradient and the expectation, since the expectation is being taken with respect to the distribution that we are trying to differentiate.

So instead of framing our equation in terms of these unknown parameters, we might try to frame it in terms of a known equation:

If we know the distribution of $\epsilon$ , we can take its derivate thus allowing us to compute the first term in eq. 12. In other words, we avoid evaluating the gradient in terms of $\theta$ and instead evaluate it in terms of $\epsilon$. This is the key contribution of the original VAE paper: the reparameterization trick..4

The Reparameterization Trick

Ok, so we have our loss function that we want to use to optimize our VAE. Recall eq. 10

Rearraigning (and simplifying a bit) we get:

So we want to minimize the KL divergence and maximize the ELBO. And we have two parameters: $\phi$ and $\theta$ so we need $\bigtriangledown_\phi$ and $\bigtriangledown_\theta$.

| We want to optimize the parameters of our model $\theta$. The gradients of the ELBO (the second term in eq. 10) w.r.t. the $\theta$ are straightforward to obtain since we known the joint distribution $p_{\theta(x,z)}$. Our gradient of the ELBO just evaluates to $\bigtriangledown_{\theta}L_{ELBO} = \bigtriangledown_{\theta}(\text{log}p_\theta(x,z))$. Here our $z$ is just a random sample from $q_\phi(z | x)$. |

The other term (the first term in eq. 10) is our KL divergence. Recall from eq. 6 that the KL divergence here can be expressed as

Which can be rewritten as:

| We need to take the derivative of this term w.r.t. $\phi$ in order to get the gradients of the variational parameters ($\phi$). But like in the previous section, we cannot move the gradient inside of the expectation since we are taking the expectation w.r.t the distribution $q_\phi(z | x)$ which is a function of $\phi$. |

So like we hinted in the previous section, our solution is to introduce the reparameterization trick: to express the random variable $z$ as a deterministic variable.

![Source: [^6]](/My-DS-Blog/images/reparameterization_trick.png)

So to summarize:

Instead of directly sampling from the approximate posterior distribution, which involves a non-differentiable stochastic operation, the trick involves reparameterizing the sampling process to make it differentiable. By applying the reparameterization trick, the gradients of the ELBO with respect to the parameters of the approximate posterior can be estimated, allowing for efficient optimization of the VAE.

Choosing the variational family for $q(\cdot)$

The complexity of the family determines the complexity of the optimization; it is more difficult to optimize over a complex family than a simple family.

| A common choice of the form $q_\phi(z | x^i)$ is a multivariate Gaussian with a diagonal covariance structure. Therefore, we will assume that the posterior is a k-dimensional Gaussian with diagonal covariance. So the posterior should take the form: |

where $\epsilon \sim N(0, I)$ and $\odot$ is the element-wise product. Recall that the multivariate normal density is defined as:

and that our $D_{KL}$ can be defined as:

Given that we have defined $q(z)$ as belonging to a multivariate Gaussian, we can use the multivariate normal density as our definition of $q(z)$. So just plugging the following into our equation for $D_{KL}$

The result:

The general form of the KL divergence for k-dimensional Gaussians is:

More Complexity: Normalizing Flows at a High Level

Normalizing flows deserves its own post, but lets briefly explain the concept.

Variational inference searches for the best posterior approximation within a parametric family of distributions. Hence, the true posterior distribution can only be recovered exactly if it happens to be in the chosen family. Above, we used a simple variational family of diagonal covariance Gaussian distributions. We know that the better the variational approximation to the posterior the tighter the ELBO. However, with such simple variational distributions the ELBO will be fairly loose, resulting in biased maximum likelihood estimates of the model parameters $\theta$. See the figure below:

![Source: [^7]](/My-DS-Blog/images/normalizing_flows.png)

Since more complex variational families enable better posterior approximations, resulting in improved model performance, designing tractable and more expressive variational families is an important problem in variational inference. As a result, Rezende and Mohamed introduced a general framework for constructing more flexible variational distributions, called normalizing flows. Normalizing flows transform a base density through a number of invertible parametric transformations with tractable Jacobians into more complicated distributions.5

Some final intuition behind the two-term loss

For standard autoencoders, we simply need to learn an encoding which allows us to reproduce the input. This means we only need to minimize the reconstruction loss, which should achieve class separation of the input samples. However, with VAEs that learn a smooth latent state representations of the input data, we want to avoid areas in latent space which don’t represent any of the observed data. So we cannot rely only on reconstruction loss.

On the other hand, if we only focus only on ensuring that the latent distribution is similar to the prior distribution (through our KL divergence loss term), we end up describing every observation using the same unit Gaussian, which we subsequently sample from to describe the latent dimensions visualized. This effectively treats every observation as having the same characteristics; in other words, we’ve failed to describe the original data.

However, when the two terms are optimized simultaneously, we’re encouraged to describe the latent state for an observation with distributions close to the prior but deviating when necessary to describe salient features of the input. Equilibrium is reached by the cluster-forming nature of the reconstruction loss, and the dense packing nature of the KL loss, forming distinct clusters the decoder can decode. This is great, as it means when randomly generating, if you sample a vector from the same prior distribution of the encoded vectors, N(0, I), the decoder will successfully decode it. And if you’re interpolating, there are no sudden gaps between clusters, but a smooth mix of features a decoder can understand.

def vae_loss(input_img: np.array, output: np.array) -> float:

reconstruction_loss = np.sum(np.square(output-input_img))

kl_loss = -0.5 * np.sum(1 + log_stddev - np.square(mean) - np.square(np.exp(log_stddev)), axis=-1)

total_loss = np.mean(reconstruction_loss + kl_loss)

return total_loss

Other Useful References

- Diederik P. Kingma, & Max Welling (2019). An Introduction to Variational Autoencoders_. Foundations and Trends in Machine Learning, 12(4), 307–392. https://arxiv.org/abs/1906.02691

- Carl Doersch. (2021). Tutorial on Variational Autoencoders. https://arxiv.org/abs/1606.05908

- Vlodymyr Kuleshov & Stefano Ermon’s notes form Stanford CS228 on VAE: https://ermongroup.github.io/cs228-notes/extras/vae/

- Rianne van den Berg’s 2021 talk on Variational Inference and VAEs- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-hcxTS5AXW0.

- https://blog.evjang.com/2016/08/variational-bayes.html

-

David M. Blei, Alp Kucukelbir, & Jon D. McAuliffe (2017). Variational Inference: A Review for Statisticians_. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 112(518), 859–877. ↩

-

Approximate inference is needed since the evidence (denominator in equation for Bayes rule) $p(x)$ is usually intractable. ↩

-

Bishop, C. (2006). Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning. ↩

-

Kingma, D., & Welling, M. (2014). Auto-Encoding Variational Bayes. https://arxiv.org/abs/1312.6114. ↩

-

Danilo Jimenez Rezende, & Shakir Mohamed. (2016). Variational Inference with Normalizing Flows. ↩