Neural Tangent Kernel

When neural networks and more general non-linear models are accurately approximated by their linearizations

- Introduction

- Motivation

- What is a Kernel?

- A Simple Illustration

- Theoretical Justification for Linear Approximation?

- Neural Tangent Kernel (NTK)

- Why is this interesting?

Introduction

Much of the research on deep learning theory over the past few years addresses the common theme of analyzing neural networks in the infinite-width limit. At first, this limit may seem impractical and even pointless to study. However, it turns out that neural networks in this regime simplify to linear models with a kernel called the neural tangent kernel. These results are significant as they give a way of understanding why neural networks converge to a optimal solution. Gradient descent is therefore very simple to study, leads to a proof of convergence of gradient descent to 0 training loss. Neural networks are know to be highly non-convex objects and so understanding their convergence under training is highly non-trivial.

In the post, we will do a deep dive into the motivation and definition of NTK and how it can be used to explain the evolution of neural networks during training via gradient descent.

Motivation

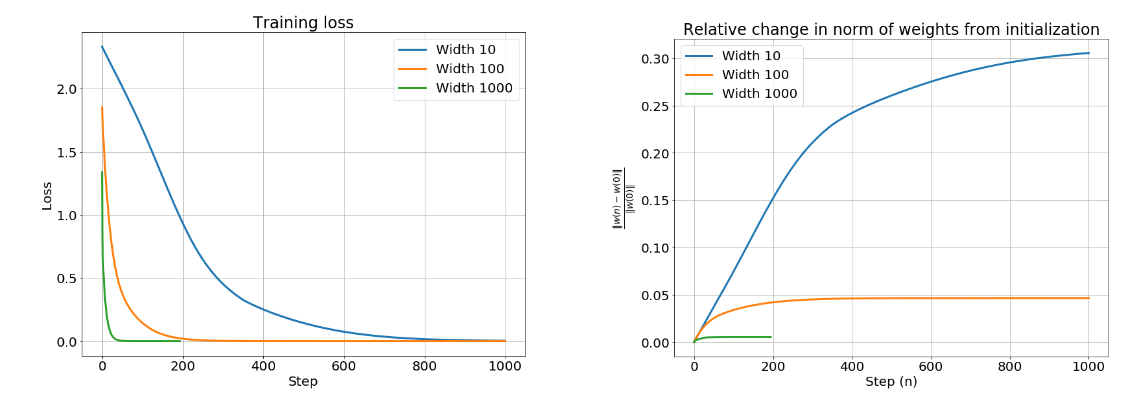

Following the popularization of deep learning beginning in the late 2010s, a series of papers were published where it was shown that overparametrized neural networks could converge linearly to zero training loss with their parameters hardly varying.1 This culminated in a a 2020 paper titled “On Lazy Training in Differentiable Programming,” where the authors coin the phrase lazy training, which corresponds to the model behaving like its linearization around the initialization.2 This can be proven quantitatively, by looking at the relative change in the norm of the weight vector from initialization:

Lets look at a simple 2-hidden layer ReLU network, with varying widths.

As we can see from the results above, training loss goes to zero for all networks, yet for the widest network, the weights barely move! It appears the approximation is a linear model in the weights. Does that mean that minimizing the least squares loss reduces to just doing linear regression?

Well no, since the model function is still non-linear in the input, because finding the gradient of the model is definitely not a linear operation. In fact, this is just a linear model using a feature map $\phi(x)$ which is the gradient vector at initialization. This feature map naturally induces a kernel on the input, which is called the neural tangent kernel (NTK).

What is a Kernel?

A kernel is essentially a similarity function between two data points. It describes how sensitive the prediction for one data sample is to the prediction for the other; or in other words, how similar two data points are. Depending on the problem structure, some kernels can be decomposed into two feature maps, one corresponding to one data point, and the kernel value is an inner product of these two features:

Kernel methods are a type of non-parametric, instance-based machine learning algorithms.

A Simple Illustration

Consider a linear function $f(x, \theta) = \theta_{1}x + \theta_2$. Like in the case of a neural network, we will initialize our parameters $\theta$s. We will then conduct a forward pass, calculate the loss function, and then propagate backwards in order to adjust our parameters $\theta$. Since our function $f$ is not parametrized as lookup tables of individual function values, changes our $\theta s$ based on a single training iteration will change the parameters for all of our observations.

This is why the neural tangent kernel is useful; at its core, it explains how updating the model parameters on one data sample affects the predictions for other samples.

Theoretical Justification for Linear Approximation?

The linearized model is great for analysis, only if it’s actually an accurate approximation of the non-linear model. Chizat and Bach3 defined the condition where the local approximation applies, leading to the kernel regime:

In words, if the Hessian divided by the squared norm of the gradient is less than 1, the gradient dynamics track very closley with gradient dynamics on a kernel machine. Put another way, if the condition above holds, it means that is little to no movement in the weights as there is no negative curvature. So how much the Hessian changes is very small relative to how much the gradient is changing. This is key, as we only change parameters slightly (if at all) and achieve a large change in predictions. This means that we obtain a linear behavior in a small region around initialization.4

Based on this equation, a key condition can be summarized as follows: the amount of change in $w$ to produce a change of in $y$ causes a negligible change in the Jacobian $\bigtriangledown _w y(w_0)$. What is key now is to understand how the quantity in (1) which we will now represent as $k(w_0)$ changes with the hidden width $m$ of our network.

Well, it turns out based on the research5 that $k \rightarrow 0$ as $m \rightarrow \infty$ . This means that the model is very close to its linear approximation.

An intuitive explanation for why this happens is as follows: a large width means that there are a lot more neurons affecting the output. A small change in all of these neuron weights can result in a very large change in the output, so the neurons need to move very little to fit the data. If the weights move less, the linear approximation is more accurate. As the width increases, this amount of neuron budging decreases, so the model gets closer to its linear approximation.

Neural Tangent Kernel (NTK)

So if the model is close to its linear approximation, ($k(w_{0})\ll 1$), the Jacobian of the model outputs does not change as training progresses. This means that $\bigtriangledown y(w(t)) \approx \bigtriangledown y(w_0)$. This is referred to as the kernel regime, because the tangent kernel stays constant during training. The training dynamics now reduces to a very simple linear ordinary differential equation: $\bigtriangledown y(w) = -H(w_{0})(y(w)- \bar{y})$ where $H$ is the NTK $\bigtriangledown y(w)^{T}\bigtriangledown y(w)$ . Lets try and derive it step by step.

Our loss function can be represented as:

And its using the chain rule the gradient can be represented as

Where the size of the first gradient term is $P$x$n_L$ where $P$ is the number of parameters in the network and $n_L$ is the number of layers. The size of the second gradient term is of size $n_L$x$1$.

If we take the learning rate to be infinitesimally small, we can look at the evolution of the weight vectors over time, and write down this differential equation:

This is called a gradient flow. In essence, it is a continuous time equivalent of standard gradient descent. The main point is that the trajectory of gradient descent in parameter space closely approximates the trajectory of the solution of this differential equation if the learning rate is small enough. Again this is because when tracking how the network parameter $\theta$ evolves in time, each gradient descent update introduces a small incremental change of an infinitesimal step size.

Now we can express how the network output evolves over time according to the derivative:

Where the red component in (5) is the NTK, $K(x, x’; \theta) = \bigtriangledown_{\theta}f(x;\theta)^{T} \bigtriangledown_{\theta}f(x’;\theta)$. This means that the feature map of one input $x$ is $\phi(x) = \bigtriangledown_{\theta}f(x;\theta)$. This is because the NTK matrix corresponding to this feature map is obtained by taking pairwise inner products between the feature maps of all the data points.

Further, since our model is over-parameterized, the NTK matrix is always positive definite. By performing a spectral decomposition on the positive definite NTK, we can decouple the trajectory of the gradient flow into independent 1-d components (the eigenvectors) that decay at a rate proportional to the corresponding eigenvalue. The key thing is that they all decay (because all eigenvalues are positive), which means that the gradient flow always converges to the equilibrium where train loss is 0.

Why is this interesting?

It turns out the neural tangent kernel becomes particularly useful when studying learning dynamics in infinitely wide feed-forward neural networks. Why? Because in this limit, two things happen:

- First: if we initialize $\theta_0$ randomly from appropriately chosen distributions, the initial NTK of the network $k_{\theta_0}$ approaches a deterministic kernel as the width increases. This means, that at initialization, $k_{\theta_0}$ doesn’t really depend on $\theta_0$ but is a fixed kernel independent of the specific initialization.

- Second: in the infinite limit the kernel $k_{\theta_0}$ stays constant over time as we optimize $\theta_0$. This removes the parameter dependence during training.

Further reading:

- https://rajatvd.github.io/NTK/

- https://lilianweng.github.io/posts/2022-09-08-ntk/

-

Simon S. Du, Xiyu Zhai, Barnabás Póczos, and Aarti Singh. Gradient descent provably optimizes over-parameterized neural networks. In International Conference on Learning Representations, 2019; Simon S. Du, Lee Jason D., Li Haochuan, Wang Liwei, and Zhai Xiyu. Gradient descent finds global minima of deep neural networks. In International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), 2019; Zeyuan Allen-Zhu, Yuanzhi Li, and Zhao Song. A convergence theory for deep learning via over-parameterization. In Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning, volume 97, pages 242–252, 2019; Yuanzhi Li and Yingyu Liang. Learning overparameterized neural networks via stochastic gradient descent on structured data. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, pages 8167–8176, 2018. ↩

-

Chizat, Lenaic, and Francis Bach. “A note on lazy training in supervised differentiable programming.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1812.07956 (2018). ↩

-

Lenaic Chizat, & Francis Bach. (2018). On the Global Convergence of Gradient Descent for Over-parameterized Models using Optimal Transport. ↩

-

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l0im8AJAMco ↩

-

Jacot, Arthur, Franck Gabriel, and Clément Hongler. “Neural tangent kernel: Convergence and generalization in neural networks.” Advances in neural information processing systems. 2018; - Chizat, Lenaic, and Francis Bach. “A note on lazy training in supervised differentiable programming.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1812.07956 (2018); - Arora, Sanjeev, et al. “On exact computation with an infinitely wide neural net.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1904.11955 (2019); - Li, Zhiyuan, et al. “Enhanced Convolutional Neural Tangent Kernels.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1911.00809 (2019); Lee & Xiao, et al. “Wide Neural Networks of Any Depth Evolve as Linear Models Under Gradient Descent.” NeuriPS 2019. ↩